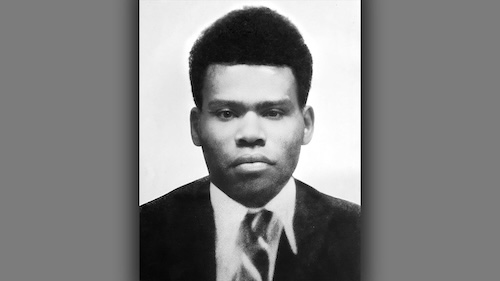

I’m moved and inspired by the story of one of our new saints (canonized today!), Peter To Rot from New Guinea. Though never ordained, he was a catechist to his people and lived a ministry that was profoundly, beautifully diaconal. He died a martyr during World War II at the age of 33:

Peter To Rot was born in the small village of Rakunai in 1912, thirty years after the first missionaries arrived on the present-day island of New Britain, now part of Papua New Guinea, in 1882. His father, Angelo To Puia, a village chief, and his mother, Maria Ia Tumul, were both baptized as adults, becoming part of the country’s first generation of Christians. Peter was the third of six children born from this marriage.

In the early 1930s, at the tender age of eighteen, Peter entered catechism school. He returned home in early 1933 to begin his ministry as a catechist, a role he assumed at the age of just twenty-one. By 1936, after three years of service, Peter To Rot had already earned the affection and respect of everyone in Rakunai and the surrounding villages. On November 11, 1936, he married Paula Ia Varpit in the parish church of Rakunai. They had three children.

In 1942, when the Japanese invaded part of what is now Papua New Guinea, one of their first acts was to imprison all foreign missionaries. With a shortage of priests (because there was still no local clergy), thousands of New Britain faithful were left without pastors to guide them and no one to guard their faith. At that crucial moment, the young catechist, then only thirty years old, rose to prominence as a giant of faith, taking on the responsibility of keeping the hope and faith of his people alive. Despite the Japanese bans on religious practices, Peter To Rot carried out an exemplary apostolate in his village and in neighboring communities, as many catechists, overcome by fear, had abandoned their ministry. Dedicated to service, he spent his time visiting the sick, baptizing children, praying with the community, preparing couples for marriage, burying the dead, and distributing Holy Communion. He often walked for more than five or six hours, facing dangers and threats from the Japanese, to secretly reach the prison where the missionaries were held and receive the consecrated hosts, which he then clandestinely distributed in the villages.

By June 1944, the Japanese knew their defeat was inevitable. In an effort to curry favor with village leaders, their authorities legalized traditional polygamy, which had been banned by the Catholic Church and the previous colonial government, for those who aligned themselves. Unfortunately, the vast majority of tribal leaders accepted the offer, and polygamy began to be practiced again.

To Rot’s response to these developments was entirely predictable: from the very beginning, he openly denounced polygamy as a pagan practice unacceptable to Christians. He used every means at his disposal to persuade Catholics to resist this practice. He knew that maintaining his position could mean arrest or death, but he could not remain silent in the face of such grave danger. He understood and taught that marital union, by its very nature, requires the indissolubility of the bond and the unity of the spouses for life.

In this new situation, Peter To Rot was ready to fight with all his strength and, if necessary, offer his life as a final tribute to God. Because of his preaching and his insistence on observing God’s law and respecting the sanctity of marriage, To Rot attracted the hatred of many local and Japanese men driven by lust. Among these were policemen, soldiers, and important men who had the power to silence him forever. Indeed, Peter To Rot was arrested and threatened on several occasions, and was always urged to abandon his apostolate and embrace the infamous practices being proposed. He was imprisoned for the last time in April or June 1945. From the moment of his arrest, he was convinced he would die in prison. The day before To Rot was killed, one of the village leaders had the opportunity to see him for the last time. It was he who heard from To Rot’s lips the catechist’s clearest and most beautiful declaration: “I am here for those who break their marriage vows, and for those who do not want to see God’s work go forward. Enough. I must die. You go back to taking care of the people. They have already condemned me to death.”

His wife, Paula Ia Varpit, also recalls her last meeting with her husband: “I asked Peter To Rot to suspend his pastoral work only once. This was on the day of his death, when I visited him for the last time in prison. I had never asked him to stop his pastoral work before, because, given his strong insistence, his deep faith, and his determination in his work, I knew he would refuse to consider such requests. Peter To Rot’s response to my plea was: ‘Don’t stop me from doing my work. It is God’s work.’”

On the night of July 7, 1945, two Japanese doctors visited the catechist in his cell. One of them gave him an injection and told him to lie down. After a while, Peter To Rot began to thrash and seemed to want to vomit. The doctor covered his mouth and held him still until he breathed his last.

St. Peter To Rot, pray for us!