The New York Times unpacks the religious journey of the GOP nominee for Vice President:

From his new home in Cincinnati, JD Vance would go to St. Gertrude to meet the friar.

It was a fitting place for the millennial aspiring politician, who was drawn to the Roman Catholic Church’s ancient ways. For years he had flirted with joining the church. Now he wanted to explore the desire in earnest.

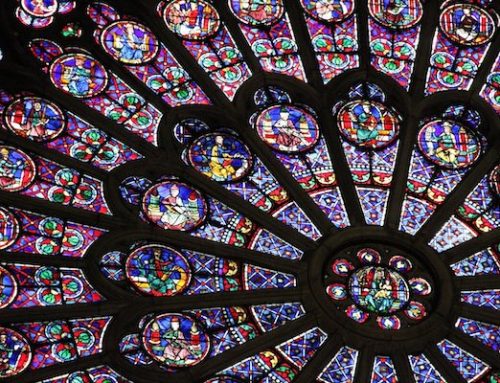

St. Gertrude Church was led by the Dominican Friars from the Province of St. Joseph, part of a religious order founded in 1216. Its sanctuary smelled of incense but felt modern, its concrete walls pierced with bright stained-glass rectangles in reds and blues.

Mr. Vance would meet with Father Henry Stephan. For months, they read works of theology, mysticism, and political and moral philosophy. Sometimes they went to coffee or lunch. It was bespoke private instruction, a hallmark of Dominicans who are known for their lives of intellect and study.

Then, one summer day in 2019, Mr. Vance, then 35, returned to St. Gertrude, this time to be baptized and receive his first communion in the Dominicans’ private chapel. The friars hosted a celebratory reception for his family with doughnuts. He chose as his patron Saint Augustine, the political theologian whose fifth-century treatise “City of God” challenged Rome’s ruling class and drew Mr. Vance to the faith.

“It was the best criticism of our modern age I’d ever read,” Mr. Vance later explained in a Catholic literary journal. “A society oriented entirely towards consumption and pleasure, spurning duty and virtue.”

Much has been made of Mr. Vance’s very public conversion to Trumpism, and his seemingly mutable political stances. But his quieter, private conversion to Catholicism, occurring over a similar stretch of years, reveals some core values at the heart of his personal and political philosophy and their potential impact on the country.

Becoming Catholic for Mr. Vance, who was loosely raised as an evangelical, was a practical way to counter what he saw as elite values, especially secularism. He was drawn not just to the church’s theological ideas, but also to its teachings on family and social order and its desire to instill virtue in modern society.

That worldview served as a counterpoint to much of his messy childhood, and meshed with his own criticisms of contemporary America, from what he saw as the abandonment of workers to the unhappiness of “childless cat ladies.” It has also infused his politics, which seeks to advance a family-oriented, socially conservative future through economic populism and by standing with abortion opponents.